實踐大學工業產品設計系擔任助理教授

Assistant Professor, Department of Industrial Design, Shih Chien University

Article of famous designers

實踐大學工業產品設計系擔任助理教授

Assistant Professor, Department of Industrial Design, Shih Chien University

I am Shi-Kai Tseng. I started my journey in design at Ming Chuan University’s Department of Product Design, and earned my master’s degree from NTUST College of Design. Through the Ministry of Education’s Overseas Training Program for Elite Artists and Designers, I went to the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London for further study. After graduation, in 2011, I started my own business in London. There, I worked on product design and development, design art, branding, exhibition curation, and other related business tasks. Currently, I serve as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Industrial Design, Shih Chien University.

1. What is the purpose of design?

Generally speaking, Taiwan society pays much attention to commercial value and efficiency. This emphasis has been extended to all areas of education, of course including different types of design. In this context, university has become a field for “professional exploration and fundamental technical training”; the only way to build technical abilities in design is to practice a lot. If that is the case, do students have opportunities to get close to the objects of their design service through industry-academia or onsite visits? I think the answer might be “No”. Therefore, “simulated” proposals based on design competition themes or topics given by teachers became the focus of training. However, when proposals and concept competitions are only carried out based on “simulation” rather than actually getting into the industry, market, and user groups, and then this continues over time, we become paralyzed and lose our passion for design; our thinking becomes ossified, considering design to just be a rigid set of processes or steps.

When I served as a judge for a large domestic design competition last year, I remember deeply that one student had two or three works shortlisted in the competition. One proposal was focused on integrating technology into a children’s educational toy. Judges were all eager to see the functioning model, which would demonstrate the software/hardware integration. Unfortunately, the proposal was only accompanied by a visual mockup, without any interface nor functional model displayed. It was such a pity. Another work presented by the student was a type of paper-constructed temporary toilet combined with airdrop aid boxes, designed to respond to recent war refugee issues. In this design, plant seeds are embedded in cardboard boxes, where excreta, acting like fertilizer, provides nutrients for the seeds to grow. Putting aside the question of whether these concepts are innovative or not, as a proposal for graduation design exhibition, the design was only a graphical presentation. It did not explore in depth questions like “How do you implement this?”, “Who are the stakeholders?”, or “Is it materially feasible?”. And there was no functioning model to confirm the design’s feasibility. With these kinds of issues, it may not be easy to gain access to domestic organizations or interested parties; it could be hard to get interviews for collaboration with users and sponsoring organizations needed for the kinds of long-term partnerships to realize the design’s true value.

Those two examples are a real representation of what is happening with design students in Taiwan: Design becomes shallow creative idea contests, without sufficient consideration of the design’s users, manufacturing, feasibility, costs, and so on. Such an approach indeed played a mainstream role 20 years ago. Now, though, I deeply feel that this is the wrong direction.

“Who the heck are we designing for? What the heck are we designing for?”

Prize-winning is just a process; it should not be an end goal!

If all our design behaviors don’t create positive cycles or receive positive feedback (by which I don’t mean temporary honors like prize-winning, but the positive feedback received from users or commercial support gained from the market), we will fall into a sense of emptiness – the emptiness of not knowing what we are designing for. Design then becomes a kind of empty aesthetic perception and conceptual evaluation. The worst thing is that with the flourishing development of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies that we see around us, aesthetic perception and concepts will become cheaper and cheaper.

2. Technology Anxiety

With the advancement of technology and tools over the past decades, we can say that Design has become an easier job, but a more difficult task as well. What makes it easier is that the barriers to entry have been lowered, and outstanding designs can be spread in a highly efficient way. People who are new to the design field can, without having to understand any background knowledge, rapidly enhance their aesthetic perception abilities just by copying. They can even create complete, above-average works with the aid of technology.

In 2016, Alibaba, China’s leading e-commerce group, initiated the Luban AI-based design tool to produce 170 million product display ads for the Double 11 Shopping Festival. It was claimed that product clickthrough rates had increased by 100%. Several years later, Luban was renamed Lu-ban; it became a paid tool for e-commerce customers to significantly reduce graphic designers’ repetitive work, and help companies shorten the time needed for product launch. Elon Musk unveiled the Optimus robot prototype on Tesla’s AI Day in August 2022; Jensen Huang announced the Project GR00T at Nvidia’s annual GPU Technology Conference (GTC) in March 2024, and declared the advent of the AI-robot era. The development of AI computing, automated production and robots has reminded us that humans have been constantly pursuing productivity increases since at least the Industrial Revolution; repetitive tasks have gradually been replaced. From production line workers, to workers in front of computers, it seems that any task that can be automated, will be automated, without mercy.

"Tasks that I hope AI can do – cooking, cleaning, laundry, taking out the trash, cleaning cat’s litter box, doing chores, and working to make money. What AI is doing now – chatting, drawing, writing, composing music, playing games… I really want to beat it up!” – Japanese Twitter user @gunka0111 on X.

Well, that won’t be the case, will it? I also want to argue that if tasks such as daily chores, work, entertainment, creation, etc. are all done by AI, what else can we do?

It is interesting that once we start thinking about this, we may find some things that can only be done by us! In terms of industrial design, in addition to fulfilling users’ needs, it is also necessary to consider Differentiation in Business”. In fact, Differentiation has been deeply embedded in the fundamental logic of human DNA. “Is there anything that we can do but AI can’t do, or will not be able to do in the near future?”

As mentioned in the book AI 2041: Ten Visions for Our Future (authors: Lee Kai-fu and Chen Qiufan; publisher, Commonwealth Publishing Company), humans’ “creativity”, “empathy” and “flexibility” are some elements that will not be able to be replaced by AI or robots in the near future. To put it another way, our value can be fully manifested in these aspects, particularly the first two – and those are precisely the qualities that a good industrial product designer should possess! And what if we could only pick one of those? Then I would first choose “empathy”, and after that, “creativity”.

What I want to express is that this is not only an era of AI, but also an era of Humanity. Being pushed by the trend of new technological development, we should eventually think in depth about humans’ value and the significance of being alive, rather than being tied up with repetitive work. This also implies that the job of design will become harder and harder than it was in the past, as it needs to emphasize more and more the Value that such design manifests. I had a student named Mitchell Hoooo who graduated in 2023. Influenced by a family member’s teaching job at a school and Ho’s own interest in music, my student had been thinking about ways to help his family. One day, an idea popped into his mind: “Why do we only use recorders for music education classes?”

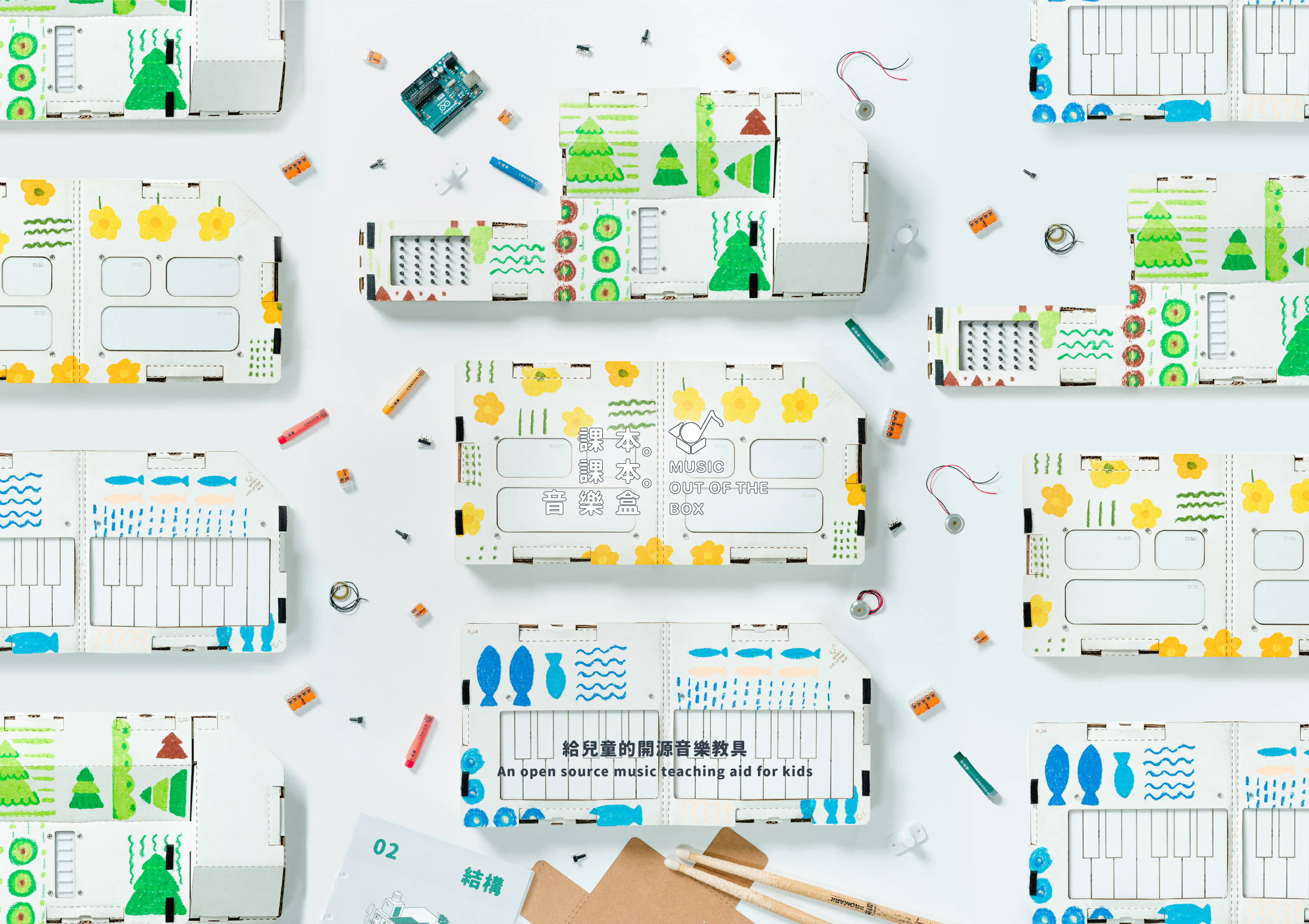

He did interviews as research, and found that considerations of affordability have caused public schools to set price limits for musical instruments. To solve this issue, incorporating contemporary trends in education and integrating three subjects of “Technology in Daily Life”, “Art”, and “Music”, he designed a set of inter-disciplinary open-source electronic musical instrument curriculum modules. With cardboard, acrylic board, and manufactured electronic components (all costing no more than NT$250), a 16-key piano, electronic drum, or electronic guitar can be created. Additionally, in the development and design process, he conducted at least two testing-oriented workshops to adjust the curriculum’s difficulty, based on the feedback given by primary school teachers and students. This design was recognized with a Taiwan Young Pin Design Award, Golden Concept Design Award, and the James Dyson Award in Taiwan. I have been thinking that this project possesses even more possibilities and room for further development; but unfortunately, Yi-Shao had other plans after graduation, and was unable to bring this design to the next stage.